John 3:1–15

Nicodemus

Winslow Homer

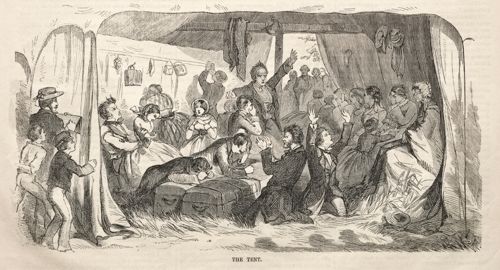

Camp Meeting Sketches: The Tent, 1858, Wood engraving, The Cleveland Museum of Art; Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund, 1942.1357.b, Photo courtesy of Cleveland Art Museum

Camp Meeting Revivalism

Commentary by Eric C. Smith

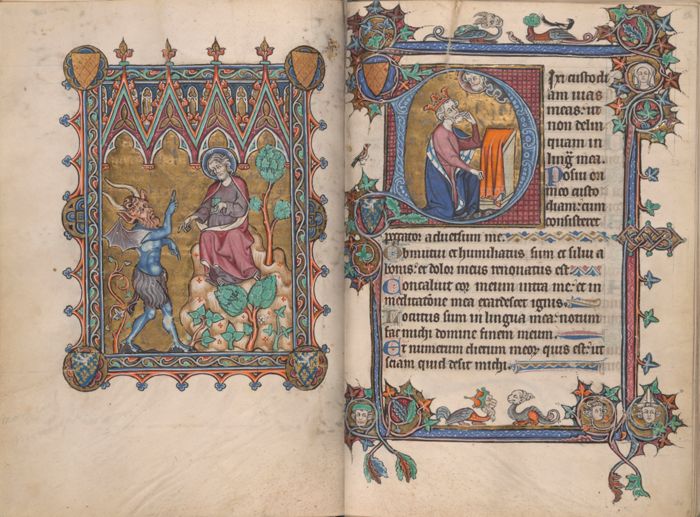

Raised a Congregationalist in New England, Winslow Homer was used to a reserved and quiet style of religious expression. His Camp Meeting Sketches, a set of woodcuts made after a visit to a Methodist camp meeting on Cape Cod in early August 1858, show hints of Homer’s wry amusement at encountering a more energetic and emotional form of worship. Commissioned and published by the magazine Ballou’s Pictorial, the woodcuts are an early example of the emerging power of images in popular media. Homer seized the new opportunities provided by illustrations in mass-media to portray and gently satirize the fervour of a camp meeting.

The gathering Homer attended in 1858 was part of an already-long tradition of religious revivalism with its origins in England, Scotland, and the United States beginning in the seventeenth century. Although the phrase is most associated with American evangelicalism in the late twentieth century, many of the early writings and sermons of the camp meeting movement dwell on the need for people to be ‘born again’—a citation of a misunderstood part of Nicodemus’s conversation with Jesus.

The idea of being ‘born again’ carries with it a host of religious and political meanings. It can signal an implicit rebuke of the person’s prior religious experiences and traditions, and it often represents an engagement with the kind of emotional and charismatic worship that Winslow Homer was portraying in this woodcut, The Tent. Here, some attendees writhe in various states of ecstasy while others display a lack of interest. Some bow in prayer, others dance and raise hands toward heaven, and still others look on from a distance. In the centre, a man—presumably the preacher—surveys and directs the moment like an orchestral conductor, but the differing reactions are a reminder that ‘the wind blows where it chooses’, and the Spirit’s movement cannot be controlled.

References

Cikovsky Jr., Nicolai, and Franklin Kelly. 1995. Winslow Homer (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Johns, Elizabeth. 2002. Winslow Homer: The Nature of Observation (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Alfonso Ossorio

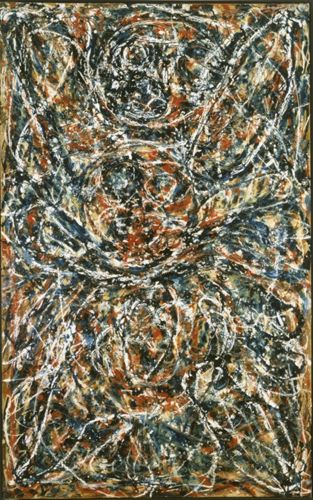

Mother and Child, 1951, Oil and enamel paint on canvas, 116.205 x 73.025 cm, The Phillips Collection; The Dreier Fund for Acquisitions, 2008, 2008.010.0001, The Dreier Fund for Acquisitions, 2008

Misunderstanding ‘Born Again’

Commentary by Eric C. Smith

The story of Jesus’s conversation with Nicodemus relies on a misunderstanding. Like the story of Jesus’s encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well that follows in the next chapter of the Gospel of John, Jesus’s discussion with Nicodemus turns on wordplay and obfuscation. The Greek word anothen, used by Jesus in 3:3, can mean either ‘from above’ or ‘again’, and Nicodemus wrongly assumes that Jesus means the latter. The same misunderstanding was not possible in the Aramaic language that Jesus and Nicodemus were presumably speaking; the confusion has been artfully introduced in Greek by the Gospel writer to make a theological point.

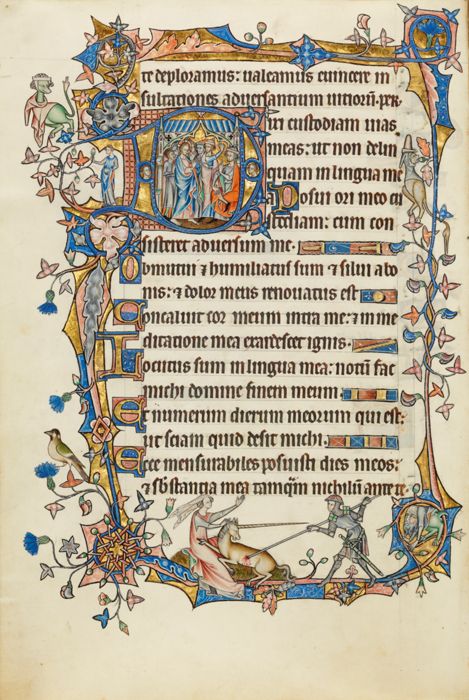

An early Abstract Expressionist, Alfonso Ossorio was among a group of artists exploring what it might mean to make works of visual art while rejecting figurative representation. His work in Mother and Child is instructive: it suggests order emerging from an inchoate background, with patterns and shapes perceptible, but only just.

It is the title of this work as much as anything that informs its interpretation. Without being told that the painting was titled Mother and Child, it is unlikely that viewers would arrive there on their own. Ossorio, therefore, takes a familiar relationship and a common feature of Christian religious iconography and teases it apart, introducing unfamiliarity and disorientation.

So too with Jesus’s words to Nicodemus. Unless Jesus had told Nicodemus what he meant, his wordplay about being ‘born from above’ would have gone misunderstood. Some explanation is necessary to make sense of it, and most of the literal sense of the meaning resides in the explanation. In both John 3:1–15 and in Ossorio’s painting, the relationship between mothers and birth is less literal than experience and visual tradition might expect, and therefore more layered than we might have assumed.

References

Friedman, B.H. 1965. Alfonso Ossorio (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.)

Ottman, Klaus, and Dorothy Kosinski. 2013. Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollack, Ossorio, Dubuffet (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Henry Ossawa Tanner

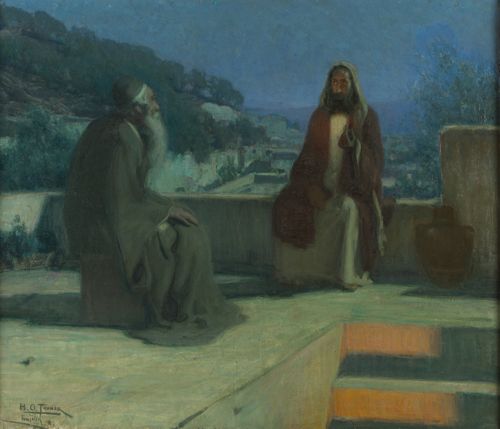

Nicodemus, 1899, Oil on canvas, Unframed: 85.56625 x 100.33 cm; framed: 114.3 x 130.175 x 8.89 cm, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia; Joseph E. Temple Fund, 1900.1, Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, 1900.1

A Subtle Light

Commentary by Eric C. Smith

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s father, an active and prominent abolitionist, was fond of the story of Nicodemus. He understood it as ‘analogous to tales of slaveholders who, in secret conversations with abolitionists, became converted to their cause’ (Bearden & Henderson 1993: 95). As one of the earliest African American painters to gain prominence in both Europe and the United States, the younger Tanner’s work frequently explored both religious themes and questions of race, often together.

During a visit to Jerusalem in the late 1890s, Tanner painted this work, using the story of Nicodemus as a ‘canvas’ to explore a set of tensions: young and old, lit and shadowed, grey and brown, and high and low.

In an earlier study for this painting, Tanner was more forthright in his use of light, framing Jesus’s head with a rising full moon like a nimbus (Marley 2012: 129, 210). But in the final version, Tanner brings illumination not only from the heavens but also from below, casting light up a staircase until it rests on Jesus’s chest and face. This stepwise use of light, Hélène Valance writes, ‘suggests the hesitations and gradual conversion of Nicodemus “coming into the light” of God’ (ibid 129).

By using light from both above and beneath, Tanner made the distinctions between Jesus and Nicodemus subtler than they had been in the earlier effort. But the painting is still a study in difference, and the two men’s juxtaposition invites comparison. Later in life, Tanner could recall ‘the fine head of the old Yemenite Jew who posed for Nicodemus’, one of several nods to the principles of the Realist movement in the painting (Bearden & Henderson 1993: 96). Meanwhile, the figure of Jesus could very nearly be a self-portrait of Tanner, with angular features and dark skin and hair. It’s one of several variances between Jesus and Nicodemus that are produced in the work, and one can’t help but wonder whether Tanner was painting while keeping his father’s abolitionist fondness for the story in mind.

References

Bearden, Romare, and Harry Henderson. 1993. A History of African-American Artists from 1792 to the Present (New York: Pantheon Books)

Marley, Anna O. (ed.). 2012. Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Winslow Homer :

Camp Meeting Sketches: The Tent, 1858 , Wood engraving

Alfonso Ossorio :

Mother and Child, 1951 , Oil and enamel paint on canvas

Henry Ossawa Tanner :

Nicodemus, 1899 , Oil on canvas

Anothen

Comparative commentary by Eric C. Smith

The meeting of Jesus and Nicodemus is rarely depicted in art. When Nicodemus is painted or sculpted, it is most often his appearance alongside Joseph of Arimathea in John 19:38–42, where the two men take Jesus from the cross, prepare his body, and give him a burial. Less common are portrayals of this conversation in 3:1–15, perhaps because it is difficult to produce compelling visual images of two people having a conversation at night. The drama of this scene is in the words, not in the setting or the action. But the dialogue holds plenty of twists and turns.

The conversation turns on a misunderstanding: the Greek word anothen, which can mean either ‘again’ or ‘from above’. Neither option is especially intelligible, if we are being fair to Nicodemus; being ‘born from above’ and being ‘born again’ both seem equally unlikely. Here the Johannine Jesus is sphinxlike and beguiling, and the night-time setting heightens the mystery. Nicodemus assumes that Jesus means that he must be born a second time, born again, but he is wrong: Jesus is telling Nicodemus that he must be born from above.

The subtext of the conversation, and of depictions of it like Henry Ossawa Tanner’s, is one of subtle difference. The Gospels describe a tension between Jesus and the Pharisees, and John 3:1 tells us that Nicodemus was both a Pharisee and a ‘leader of the Jews’. But in this passage animosity gives way to curiosity; Nicodemus and Jesus speak theologically together. As modern scholars reassess the portrayal of Pharisees both in the New Testament and in historical reconstructions, a story like John 3:1–15 emerges as historically plausible: Pharisees individually and as a group seem to have held varying and shifting perspectives on Jesus, and might have seen him as an ally as much as an opponent. The subtlety of the portrayals in Tanner’s painting anticipate this modern scholarly reconsideration, as he portrays Jesus and Nicodemus engaging with each other with equality, generosity, and curiosity.

Jesus’s mysterious words muddy the traditional logic of birth, and so does Alfonso Ossorio’s Mother and Child. Nicodemus is confused by Jesus’s wordplay in 3:3, and Jesus responds that ‘you must be born from above’ in 3:7. But Nicodemus’s incredulity remains; in 3:9, he understandably asks, ‘How can these things be?’. Nicodemus is struggling to reconcile Jesus’s words with what he knows already. Ossorio’s painting, an Abstract Expressionist take on the very traditional subjects of mother and child, holds the same tension; we know how the relationship between a mother and a child ought to look, and we know how to recognize its iconography, but Ossorio refuses to be as straightforward as our expectations demand.

The reception history of this passage is rich. Tens of millions of people have thought of themselves as ‘born again’, taking the double entendre of 3:3 to refer to a spiritual rebirth, and fostering a Christian movement that has stretched from the seventeenth century to the present. Winslow Homer witnessed and captured one scene from that movement, in a tent revival in a camp meeting in 1858, in all its spirit-fuelled fervour. Though Homer’s perspective is bemused and somewhat editorial, it also captures kinetics of religious expression and zeal that already crackle in Nicodemus’s conversation with Jesus.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus is always a step ahead of everyone else, wrangling truths and understandings that the other characters in the story struggle to grasp. The use of anothen in this passage is a clear example of this pattern; the double meaning in Jesus’s words creates a disruptive and productive confusion from which a new understanding emerges. Millennia after their encounter, the conversation between Jesus and Nicodemus continues to drive religious revival movements and personal experiences with Jesus’s words, whether understood as ‘you must be born from above’ or ‘you must be born again’.

References

Sievers, Joseph, and Amy-Jill Levine (eds.). 2021. The Pharisees (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans)

Commentaries by Eric C. Smith